|

|

|

|

September

30, 2005: Odd Lots September

30, 2005: Odd Lots

- There's a new plugin for Skype that manages a video stream,

so if you want to have an n-way video conference call on Skype,

just install Festoon

and a Webcam and you're good to go. Although I haven't tried it

yet, I keep thinking of the nerd video conference in Galaxy

Quest; it might be fun, if yet another way to kill time.

- I got the dustjacket art for The

Cunning Blood, and if you want to download it for a look,

it's here.

- Frank Glover sent me a couple of very nice images from Cassini,

including close-ups of the surface of Tethys

and little Hyperion.

Hyperion is an odd one; note the way it looks like about half

the visible face has settled as though something inside melted

and ran off. This may be Hyperion's "death

star crater" much like the one on Phobos.

A number of minor bodies in the solar system have an enormous

crater somewhere, and I've heard it speculated that most such

bodies have taken a hit that was just below the energy needed

to shatter them. Our own Moon has Mare Orientalis, though perhaps

the best one of all is the one on Mimas.

- The (very) long-awaited Firefly movie Serenity

opens today, and in celebration (alas, I can't go until next week!)

I'll cite a pretty damned sharp realization of the

starship in Lego. The trailers were pretty compelling, as

was a half-hour promo show on the Sci Fi channel a few nights

ago. Here's hoping the film will allow Joss Wheadon to keep the

Firefly franchise alive. It makes every Trek franchise

TV show look pretty sick by comparison.

|

September

29, 2005: Was JFK a Jelly Doughnut? September

29, 2005: Was JFK a Jelly Doughnut?

Most people have heard about President John F. Kennedy's famous

1963 address in Berlin in which he stated (in German) "Ich

bin ein Berliner." He was attempting to show solidarity with

those living in Berlin while the Soviet Union was attempting to

intimidate the West into handing over those parts of Berlin that

the USSR didn't already control.

For some years I've heard that the statement was grammatically

incorrect: He should have said "Ich bin Berliner," because

the indefinite article "ein" is generally used with inanimate

objects. In most of Germany, a "Berliner" is a sort of

pastry, something like a bismarck with jelly inside. So saying "Ich

bin ein Berliner" could be interpreted as "I am a jelly

bismarck" or "I am a jelly doughnut." I always used

the analogy that it was like saying "I am Danish" versus

"I am a danish." (Topologically, a Berliner pastry is

not a doughnut, though that's usually how it's characterized.)

Wikipedia's

article on the speech declares that this is an urban legend,

begun in Florida in the 1980s. Apparently no one in Berlin thought

it peculiar enough to mention at the time. I asked Pete Albrecht

about this, since he was born in Germany and probably has a clue.

The truth is that the sentence swings both ways, and can mean either

"I am from Berlin" or "I am a jelly bismarck."

(One wonders what the Iron Chancellor would have thought of his

name being applied to a pastry puff stuffed with jelly.) Proof that

somebody somewhere got the joke is present in this

item (in German, but you can babelfish it) which is a round

rubber pastry that says "Ich bin ein Berliner" in JFK's

voice when pressed. (Had I designed it, I would have had the rubber

Berliner say, "I am John Kennedy.")

Apparently, Berliners don't call Berliners "Berliners,"

but rather Pfannkuchen

(literally, pancake) which, alas, my Oxford German dictionary

defines as "doughnut." Pete points out that it's a good

thing he wasn't speaking in Hamburg or Frankfurt. ("Ich bin ein

Hamburger!" "Ich bin ein Frankfurter!") Camelot might

never have been taken seriously again.

|

September

28, 2005: Electronic Paper Developer Kits September

28, 2005: Electronic Paper Developer Kits

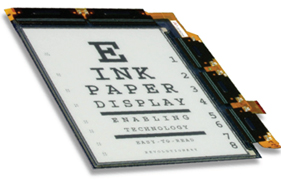

I'm

sure you're getting tired of hearing me say this: If ebooks have

any future at all, it'll be with displays having the optical characteristics

of paper. Such displays are being developed, but they're still a

ways off from where they need to be. The big fly in the ointment

is refresh time (the time to write a full-page image to the display),

a parameter that is still so awful that electronic paper vendors

are hesitant to publish it. The displays are actually mechanical

in nature (tiny dye beads must be forced to rotate to switch a pixel

from "on" to "off") and this means refresh times

on the order of seconds, not milliseconds. I'm

sure you're getting tired of hearing me say this: If ebooks have

any future at all, it'll be with displays having the optical characteristics

of paper. Such displays are being developed, but they're still a

ways off from where they need to be. The big fly in the ointment

is refresh time (the time to write a full-page image to the display),

a parameter that is still so awful that electronic paper vendors

are hesitant to publish it. The displays are actually mechanical

in nature (tiny dye beads must be forced to rotate to switch a pixel

from "on" to "off") and this means refresh times

on the order of seconds, not milliseconds.

I'd be happy with an ebook display that flipped a page in a second

or less, and supposedly these have

been demonstrated in the labs. (Demonstrated to whom?) Actually,

I'd be happy just having some crisp numbers on page refresh, but

I haven't spotted any online.

Those who are really curious can find out from personal

experience: E-Ink will be releasing electronic

paper developer kits this fall. The kit includes a 6" portrait-mode

800 X 600 SVGA electronic paper display module, plus a GumStix X-Scale

single-board controller running Linux. Driver software is written

in gcc, and the kit includes an ebook reader as a demo application.

Sounds like great fun, and you can put it in a box and have an ebook

reader when you're finished messing with it...assuming you're willing

to pay $3000 for the privilege. More pictures and some nice technical

figures on LinuxDevices.

Still, it's encouraging that E-Ink is comfident enough in their technology

to offer a commodity developer kit. It may take a couple of years,

but we'll have electronic paper sooner or later.

|

September

27, 2005: Odd Lots (Some Very Odd) September

27, 2005: Odd Lots (Some Very Odd)

- If you've ever passed by an abandoned amusement park and wondered

how it looked inside, Illicit

Ohio can be engrossing, especially if you're from or currently

living in Ohio. I used to walk Mr. Byte through the overgrown

remains of Santa's

Village in Scotts Valley, California, which was later razed

and Borland's palatial HQ built on the site. Like a goof I took

no pictures, but it was a profoundly weird place, complete with

stoned squatters and feral chickens pecking in the dirt in and

among the rusting kiddie rides.

-

The Wall Street Journal reports that

there is now so

much public nudity in Germany that German nudist clubs—which

invented the field back in the 1930s—are dying out.

-

Pete Albrecht wrote to tell me that he had learned

a new word: presenteeism,

which is the opposite of absenteeism, and describes the habit

of some to stay at the office even when there's nothing to do.

This is a problem in Japan,  but

is almost unheard of in Europe.

- Also from Pete comes a pointer to a

news item about a mad weatherman (why should scientists have

a lock on the franchise?) who's convinced that the Japanese mafia

is using secret Russian Cold War superweapons to hammer the US

with killer hurricanes. Here's

his page. You decide. (I already have, heh.)

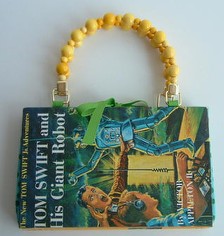

- Finally, both Bills Leininger and Higgins sent me an item (at

right) that's the ultimate retro teen-geek gender-bender status

symbol: A

purse made out of a genuine copy of Tom Swift and His Giant

Robot. I hate to be caught speechless...but sometimes

it's hard to avoid.

|

September

26, 2005: How to Spam Jeff Duntemann September

26, 2005: How to Spam Jeff Duntemann

I've been receiving email spam since almost before there was email

spam, and I've gotten pitches for it all: Sex, drugs, mortgages,

used golf balls in bulk, and romantic accordion music. All in vain.

I am uninterested in porn, I've already paid off my mortgage, I

don't golf, and I tried playing the accordion when I was seven—and

could barely stand with the huge damned thing strapped to my chest.

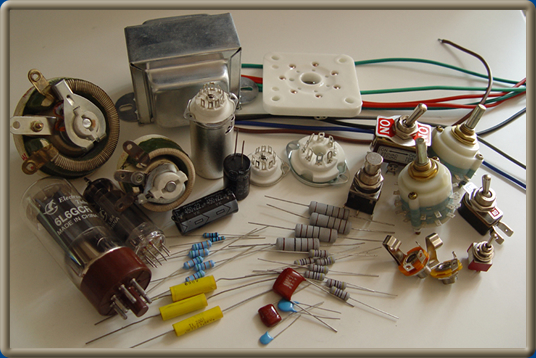

Nonetheless, a day or two ago I got a spam that made my heart race,

at least a little. The pitch was conventional, but the graphics

were arresting:

Hey, when was the last time you got spammed

with a photo of an 813 power tube socket?

I'll be fair to the company in question, a Chinese exporter: They

had apparently read my 12V tube page and somehow misconstrued me as

a dealer in electronics parts. So calling them spammers may be a little

harsh, even though I really don't like unsolicited commercial mail.

I only mention it because they figured out how to get my attention

to a degree that no other spammer ever has, and that's an accomplishment

all by itself.

|

September

25, 2005: Ebook Anguish, Part 7: Speculations September

25, 2005: Ebook Anguish, Part 7: Speculations

It was back during my tenure at Xerox that I first heard the marketing

expression, "Eating your own babies." Xerox had the problem

that its newer copier generations were always better than their

older ones, while also being cheaper. The cheaper machines drove

those plodding old cash generators off the market. In some parts

of the company, this was reason enough to want to slow down innovation.

Fear of "eating their own babies" is the reason that

the big New York houses are charging the same for their ebooks as

for their print books (while encumbering their ebooks with more

and more aggressive DRM) and when only the geekiest among us shell

out, the publishers shrug and say, "I guess there's no ebook

market."

Meanwhile, in SF, fantasy, and other forms of genre fiction from

middle and small press, $5 and $6 ebooks are thriving. A

small company exhibiting across the aisle from Paraglyph at

BEA 2003 told us that they would be selling ebooks shortly, and

now it's a major part of their business. (I confess, it's a business

I don't fully understand.) Could the New York houses succeed if

they tried the same things the same ways? I'm not sure. I think

that the genre fiction people do well for these reasons:

- The most rabid genre devotees are people who read all the time

and want a steady stream of new material that is familiar but

not boringly identical. Series and authors are what sell; individual

titles tend to rise, swim, and then sink, with only a vanishing

handful becoming "classics." In a sense, the readers

are buying the genre rather than individual books.

- Genre fiction does not need technical figures, tables, or illustrations.

This makes ebook files smaller and display presentation easier,

especially on marginal devices like smartphones.

- Genre devotees have their own word-of-mouth network consisting

of chat rooms, fan sites, email lists, Web rings, and even meatspace

conventions. I've been attending SF conventions for over thirty

years and thought it was an SF fluke, but it's not. There are

romance conventions, mystery

conventions, and Westerns

conventions. Promoting at these conventions is much more cost-effective

than using conventional mass media, but outside the genres these

word-of-mouth networks are pretty sparse.

- Genre fiction has a better grasp of what sells than mainstream

fiction and nonfiction. The big New York houses must therefore

rely on blockbuster bestsellers to pay for all the books they

publish that nobody wants.

Genre fiction seems made for ebooks. The business model

pioneered by Jim Baen—co-opt the file-sharing process by using

free ebooks as bait and brand-builders—may work because all

of the books are built on a shared culture. Conventional nonfiction

and literary fiction don't have that common ground. The people who

read popular history are not necessarily the same people who read

popular science, or political analysis, or biography. This makes

it a lot tougher to "use the matrix to sell the matrix"

because not all titles are part of the same matrix.

Publishers who can succeed with ebooks may be those fitting the

following specs:

- They allow themselves to be defined by their readership; in

other words, they specialize in a single topic area of interest

to an identifiable demographic. If you serve (and understand)

the audience for popular history, don't try to sell cookbooks.

- They earn respect from their readership by knowing their topic

deeply, and in turn treating their readership with respect.

Think Tim O'Reilly.

- They keep their costs low by eschewing flashy infrastructure

and refusing to bid up the big names to the point where author

advances bankrupt them.

- They keep ego out of their business plans.

I don't know about you, but this doesn't sound like New York to

me. What this means, of couse, is that small and middle press will

lead the way. The New York houses will embrace ebooks when doing

so becomes a competitive necessity—like, when the smaller houses

have already eaten their lunches and have begun to circle their

dinners. We're still a few years off, but that's ok. We need to

work on the readers and the file formats.

In the meantime, yee-hah! It's the Wild Wild West in the publishing

world again!

|

September

23, 2005: Ebook Anguish, Part 6: The Tip Jar September

23, 2005: Ebook Anguish, Part 6: The Tip Jar

Death attracts attention. So does giving stuff away. Back in the

late 90's The Coriolis Group (my late and lamented publishing company)

licensed a number of its staler titles to a startup that was trying

to sell ebooks. I don't think we made much money on the deal, and

the startup eventually croaked. The ebooks that they created are

still freely kicking around the Web and Usenet, and every so often

I get an email from some guy who lifted The Delphi Programming

Explorer somewhere, and told me, "That was a really

good book! What else have you got?" And so a very dead

book published in 1995 still helps me sell my assembly book and

Wi-Fi Guide in 2005. Wow.

I've seen people give ebooks away and make money two ways:

- Give away your old stuff to sell your new stuff; and

- Give away your new stuff and ask for voluntary contributions.

#2 is actually the ancient shareware concept applied to ebooks,

and as dicey as it sounds, it has a peculiar logic when applied

to absolutely unknown authors, especially if they're reasonably

good writers. The logic is this: If nobody will publish your work,

you lose very little by releasing it freely on the Net and asking

for spare change. It's not earning any money on your hard drive,

so any money you earn is gravy—and if it's not totally horrible,

it will begin to generate a reputation for you, in a field where

reputation is virtually everything.

Aspiring novelist Roger Williams tells the

story on K5 about how he released his first SF novel for free

distribution, and asked politely for donations in his electronic

tip jar. (A Web "tip jar" is a button leading to a program

operated by PayPal allowing small sums to be sent to the tip jar

owner. Amazon has something

similar.) It's a long, detailed discussion, and worth reading

closely, including the (many) comments. In three months he collected

$760 and (more significantly) was mentioned favorably on both K5

and Slashdot. This isn't bad for an unknown, and I should point

out that $760 is $760 more than I've made on my SF novel.

(This should change in coming months. I hope.)

However, the real master at monetarizing free ebooks is SF's own

Jim Baen of Baen Books. Some

years back (when ebooks were still pretty exotic) Baen Books established

the Baen Free Library,

with Eric Flint as coordinator. Go back and read that link; Eric

explains it far better than I could. But in short, turning older

titles loose helps sell newer titles. It gets people hooked on series.

It makes people loyal to your line. It gets attention.

Baen Books does other interesting things with SF, like their

Webscriptions system, through which enthusiasts can buy (in

serialized form) SF novels a chunk at a time, before they appear

in print. But I think it's their use of free ebooks to generate

interest (and therefore sales) in print titles that will have the

most influence on the future.

Skeptics may well ask: Is this really a business model? Can it

scale? Can it be applied to other fields? Does it have a future?

All good questions. I'll take them up tomorrow.

|

September

22, 2005: Ebook Anguish, Part 5: Business Models September

22, 2005: Ebook Anguish, Part 5: Business Models

Recapping yesterday's entry: After subtracting the inevitable ego

issues, the core problem with ebooks as products is that there is

no business model. I'm not saying that the ebook business model

is flawed. I'm saying that it's absent, and that terrifies

even well-behaved publishing execs who are not Right Men and might

otherwise embrace ebook publishing. These are the publishing people

who aren't half insane about the possibility of getting ripped off.

They're worried about making money.

I understand—and sympathize. I myself don't have a magic business

model to unveil here. What I want to do for a day or two is talk

about some of the ways that people are trying to find it, with greater

or lesser success.

The one I admire most, hands down, is O'Reilly's Safari

subscription service. Most programmers and network guys are

familiar with it. It's brilliant because it doesn't try to preserve

the print book business model, and it takes into account the peculiarities

of its own market. Basically, for a monthly fee, you can do very

precise full-text searches on a large library of computer books

from O'Reilly and several other publishers. Your subscription entitles

you to choose a certain specified number of books, which reside

for a period of time on your virtual bookshelf on ORA's servers.

The more you pay, the bigger your shelf. When your shelf is full,

you can either buy a bigger shelf or swap out one book for another.

Books must remain there for at least 30 days before being swapped.

Your subscription entitles you to download up to five printable

chapters (not whole books) per month, and "download tokens"

roll over for 90 days. You can buy additional download tokens if

you want them. A subscription includes a 30% discount (35% in some

cases) for print books ordered through Safari. The package I describe

here (Safari Max) goes for $20 per month.

Safari works as well as it does because the unit of demand for

computer books is the chapter, not the book. (The "album

vs. song" issue in music is similar.) Although I've read a

handful of computer book tutorials from cover to cover, mostly I've

zeroed in on the chapter that explains what I need to know right

now. A chapter-oriented business model wouldn't work as well for

other nonfiction fields, where you're dealing with a history (like

The

Great Influenza) or a gradually established position.

Some will argue that Safari is an information service, and not

an ebook publisher—but if that's the business model that works,

so be it. I'll counter-argue that they're making print books available

in searchable, nonphysical form, so it really is ebook publishing.

I guess that what O'Reilly has actually done is turned print books

into a huge online help system. Given that print computer books

are an "offline help system," this was the logical next

step.

To summarize on Safari: It's easy to sign up and pay for, it's

relatively cheap (how much have you spent on O'Reilly print

books in the last few years?) and not trivial to pirate. Since programmers

are already used to squinting at on-screen man pages and help windows,

the lack of an easy-on-the-eyes reader isn't a killer. Particularly

useful chapters may be printed. I don't think I can point to any

serious flaws in the system.

Computer publishing is probably a special case. Computer books are

among the two markets I know of where people are (reasonably) willing

to read ebooks. The other is genre fiction, especially SF, fantasy,

and mystery—and that's where I'll pick up tomorrow.

|

September

21, 2005: Ebook Anguish, Part 4: DRM September

21, 2005: Ebook Anguish, Part 4: DRM

Read

an ebook aloud to your kids, go to jail.

Yeah, right. Like to see them try that. But I'm not kidding: According

to the fine print

of Adobe's Glassbok reader EULA, reading one of their ebooks

out loud is an actionable violation of the publisher's rights. I

guess we're so far down the DRM rabbit hole that DRM itself (and

in its shadow, the whole idea of copyright) has begun to look ridiculous.

What are these people thinking?

Actually, that part's pretty simple. DRM is the clown show it is

for two reasons:

- Big Media is dominated by Right

Men who cannot stand the thought that anyone is ripping

them off. Right Men never doubt themselves and cannot tolerate

humiliation, and for a grubby pre-teen to download a DRM-cracker

from Russia and free up a stolen ebook is a species of humiliation.

I'm not exaggerating here. Book publishing is full of Right Men.

I know a fair number of them, and usually cross the aisle at trade

shows when I see them coming.

- DRM is a last-ditch defense of the only business model that

existing print publishers understand. The print books business

model doesn't work for ebooks, but we don't have a new business

model yet.

It's as simple as that: The ebook industry doesn't exist because

we really don't know how to make money on them. Yes, there are reader

problems. Yes, there are format problems. And yes, DRM is offputting

to consumers. But without confidence in a business model for e-publishing,

the big guys will either take a pass, or post armed guards outside

their content.

Ebook DRM itself is for the most part beneath contempt. Microsoft's

.lit format has been cracked several times, and cracker utilities

are easily available on the Web. I've heard that Glassbook has been

cracked, though I've not seen the cracker. In a pinch, the pirates

can always take screenshots of each page and OCR them. (This is

the ebook equivalent of audio's "analog

hole" and it's

been done.) As with software activation schemes, ebook DRM only

annoys honest people who are willing to pay for content, and drives

away potential customers who feel like the whole thing is an insult

and a ripoff.

On the other hand, this is good news: While the Right Men sell

crippled ebooks for as much as (or more) than paper editions, or

just sit out the dance, the rest of us can figure out how the future

will work.

One thing you need to understand is that the print books industry

itself has a weird business model that makes people who sell coffee

makers or can openers say, WTF? I've spoken of this before

and won't take much time here, but books are basically sold on consignment,

and a huge number of paper books end up either pulped before

they're read and written off or basically given away at or under

manufacturing cost—which we call "remaindering."

This doesn't happen because publishers make mistakes. Publishers

assume that a given percentage of their printed books will

be destroyed and make no money, and factor that into their operations.

In other words, it's a part of the business model.

I see that this series may take a few more entries than I thought,

and I'm about out of space for today. I'll return to the issue tomorrow,

by looking around to see who's trying what in the ebook world.

|

September

20, 2005: Wireline Anguish September

20, 2005: Wireline Anguish

A quick aside from my current discussion of ebooks: I just got

home from a

radio appearance on NPR's Kojo Nnamdi Show, doing the noon-to-one

hour on his "Tech Tuesday" segment. The show is out of

American University in Washington, DC, but many NPR affiliates carry

it. NPR bought an hour's time at a recording studio here in Colorado

Springs so that I could talk with Kojo on a high-quality ISDN phone

line. This makes it sound like I'm actually in the studio with him,

and NPR is very fussy about the quality of their audio.

I like radio appearances, and have been on Kojo's show before.

We were about halfway through the hour, and we were having a lot

of fun, talking about how to degunk Windows and taking questions

from listeners, when suddenly the line went silent. No warning,

just...dead.

At the same moment, the studio's ordinary landline phones went

dead as well. The studio's engineer quickly got on his cell to NPR

in Washington, and they got it set up so that I could return to

Kojo's show through my cellphone. Needless to say, quality was not

especially good, but it was the best we could do.

What happened? It was infuriating, and almost a movie cliche: They

recently began building a new office complex across from the studio's

location, and the contractor was out there was a great big trenching

machine. (If you haven't seen one of these, picture a truck-sized

chainsaw for dirt.) Well, the trencher was digging a run for water

lines, and for reasons unclear, nicked the buried Qwest cable bringing

phone service to that whole area. Many, many phone lines were severed,

and I wouldn't want to be that contractor about now. ("Always

call before you dig!" "But I wasn't digging! I was just

trenching!")

Apart from the fact that it was a diabolically unlikely coincidence

(sort of the flipside of my

1923 penny story) it illustrates how vulnerable our high-tech

world is to relatively simple mechanical mayhem. The fact that one

minimum-wage doofus on a trencher machine could cut phone service

to an entire neighborhood makes ubiquitous wireless sound real

good—though sheesh, I would have settled for telephone poles!

|

September

19, 2005: EBook Anguish, Part 3: Formats September

19, 2005: EBook Anguish, Part 3: Formats

There's a ton of public domain ebooks out there—see Project

Gutenberg if you've never been there. They have about 16,000

completely free ebooks ready to read or download. All of them are

in plain text, even the ones supposedly in HTML. Now, Rasselas

was hard enough to read when expertly set in reasonably large type

in the Penguin edition I had in college. In raw text, without even

HTML headers for the chapter titles, it was painful. Typography

matters. (Nobody seems to believe this but me.)

Virtually all of the free ebooks out there are simple text files,

with almost no formatting. I thought at first that this might be

because typography requires a certain nontrivial amount of human

labor, but it's not as much as you might think, and there are clever

programs like TeX that can do about 80% of the layout automatically.

I'm sure that there are plenty of typography freaks like me who

would massage the wrinkles out of that last 20% and contribute the

layouts to the public domain, but it won't happen. It won't happen

(at least not right now) because there's no standard format for

a typeset ebook. To benefit the greatest number of people, Project

Gutenberg and its brethren leave all of their text as...plain text.

Most people believe that the reader problem (yesterday's entry)

is serious, and most people believe that the DRM problem (to be

taken up shortly, with some luck, tomorrow) is serious. Nobody seems

to believe that the current chaos in ebook formats in serious, but

it's one of those submarine issues that nobody sees until it's too

late.

There are at least ten viable typography-enabled formats for ebooks

right now. Wikipedia's

entry on ebooks provides a good summary, though I don't consider

things like SGML or XML "formats." Of those ten, four

are the major players: Microsoft

(.lit), Adobe

PDF, EReader, and

Mobipocket. For the narrow

domain of computer books, compiled

HTML Help (.chm) is also a player, but it's unknown outside

its home turf. Although there are some (very) minor players establihed

as open standards, all of the truly successful ebook formats are

proprietary and sconnected with particular ebook reader software.

As best I know, none of the readers for the four biggies will load

and display any of the other three readers' data formats.

This forces publishers to either choose a reader package to support,

or to mess with two, three, or four different document-creation

processes—and pay for a document creation suite for each one.

(There are some free ways to create PDF files, though most people

use Acrobat.) Worse, consumers have to download and install more

than one ebook reader to ensure that they can access the full range

of published ebook titles.

You can argue that DRM (more on which tomorrow) is the real issue

here: Publishers want strong DRM, and each reader package has its

own proprietary DRM scheme. I'm less sure about that. I'm pretty

sure that the majors all want to dominate the ebook business and

thus "own" ebooks the way Microsoft owns operating systems.

This makes interoperability about as popular among the lead vendors

as centipedes in a sleeping bag.

As long as this situation holds true, the process of reading ebooks

cannot "melt into" the computing experience the way the

process of reading the Web is melting into the computing experience.

We got the Web because HTTP is an open standard, Microsoft's efforts

to subvert it notwithstanding. Open

standards for ebooks have been proposed, but nobody's jumping

in to embrace them.

As long as this stalemate continues, an awful lot of people and companies

will sniff at ebooks as yet another geekoid gimmick. I'll continue

the discussion tomorrow (or soon) with the key issue of ebook DRM.

Until then, I'll leave you with this: DRM is not a disease but a symptom,

and the disease itself is the lack of a business model for ebook publishing.

There are ways to make money in ebooks, but the techniques are contrarian

in the extreme, and not the sorts of things that the Right Men who

run Big Media are likely to embrace any time soon. And as should be

obvious (but which I will explain when I conclude) that may be the

best news of all.

This came up kind of quickly, but it looks like I'm

going to be on Kojo Nnamdi's "Tech Tuesday" show tomorrow,

9/20/2005. The show is carried by a lot of NPR affiliates, and is

broadcast live at 12:00PM Eastern time, so it's 11:00 AM central and

10:00 AM mountain. We're going to be talking about degunking this

time, and Kojo's very sharp and always a lot of fun. Tune in if you

can.

|

September

18, 2005: EBook Anguish, Part 2: Headaches September

18, 2005: EBook Anguish, Part 2: Headaches

For the last ten or twelve years, I've bought fiction mostly in

hardcover or trade paperback format. Prior to that, most of what

I bought was in pocket book format. I thought I was just impatient,

but there was more to it than that. A year or two ago, I was reading

Nancy's Kress' pocket format biomedical thriller Stinger,

and caught myself wishing that I had it in hardcover. What I wanted,

50-something bifocaler that I am, was simply larger type.

So it isn't just ebooks that give readers headaches. The problem

of reflected vs. generated light is now well understood, and people

are starting to realize that contrast and viewing angle matter a

lot as well. Most of you who are interested in ebooks at all are

probably aware of recent advances in "electronic paper,"

a purely reflective display technology with the viewing angle of

paper and almost all of the contrast. Xerox led the way with its

Gyricon technology, but the

market leader today is E-Ink. I've

seen the technology demoed at trade shows, and it's extremely impressive.

I don't know how expensive it is to manufacture, but I think that

if the demand were there for mass production, it could be made very

cheaply—and it would allow me to make the type any damned size

I wanted.

Sony actually introduced an E-Ink based ebook reader for the Japanese

market in March 2004, and the display technology reviewed well.

Predictably, Sony killed the

LIBRIe reader by building ridiculous scorched-Earth DRM into

the system, and forbidding people to load their own content into

the box. (This is Sony's usual path toward also-ran-hood. Why doesn't

somebody just buy them and part them out so we won't have to watch

them commit techno-hara-kiri yet again?) What LIBRIe proved is that

E-Ink can be made right now, and read without headaches. That problem's

been solved. However, under that problem in the Great Big Sock Drawer

of Unanticipated Hassles lay another, subtler one: The reading experience

is not the same as the computing experience. A display that

works swimmingly on a computer will not work as well for reading

as a display engineered to be read, and vise versa.

Electronic paper holds its very crisp monochrome images in the

absence of applied power (like paper) but the displays are very

slow to refresh. Animation just isn't in its bag of tricks. That

doesn't matter in any but certain technical books offering simulation

or animated graphs; lord knows I do not want animated gif-oids

bouncing around my book pages. Electronic paper in color is well

along, but when reading text in bulk I want b/w and gray scale,

not color. The difference is crucial: Gorgeous full-color coffee-table

books are meant to be looked at, not read.

I don't know if faster electronic paper can be made; I'm sure its

creators are trying. In the meantime, there is yet another concept-killer:

People do not want to lug a separate reader around with them. This

is why early dedicated ebook readers like the $500 Rocket

EBook tanked on delivery: It was yet another fragile thing in

the briefcase to be learned, protected, and lugged around. People

are going blind reading ebooks on their cellphone displays because

their cellphones are always with them. I wouldn't try that, but

I've seen it done; my physician cousin Dr. Greg Toczyl has the

entire freaking PDR on his smartphone. (I guess when you need

the PDR, you need it right now, so at least he has an excuse.)

My compromise solution is this: Merge the reading and computing

experience into one device by giving that device two displays. Picture

a laptop (or better still, a convertible like Lenovo's

X41) with a conventional color LCD on one side of the hinged

lid, and an electronic paper display on the other. The electronic

paper display is on the outside, but if you need to compute, you

pop it open like any laptop and get to work. (With a convertible,

you can do it either way.) The same computer stores and processes

both ebooks and conventional data, but it renders ebooks on the

slower but sharper and easier-to-read electronic paper display.

Having seen and handled the X41 (see my entry for August

20, 2005) I'm sure this would work. Sooner or later it will be

done, and if people get used to smaller tablets like the OQO

it might just catch on big. My point is that the ebook headache problem

could be solved if manufacturers felt that the market was there. The

market isn't there yet, and those problems are even gnarlier.

More tomorrow.

|

September

17, 2005: EBook Anguish, Part 1 September

17, 2005: EBook Anguish, Part 1

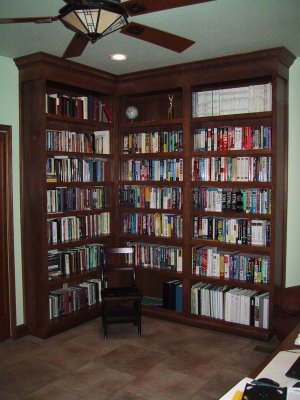

When

I built my house here, I set myself an interesting challenge: To

keep my three largest and most-used book categories (computing,

religion, and general reference) in my office, and limit myself

to what will fit on the shelves. I have a lot of shelves in this

one room (what you see at left is only about half of them) but I

also buy a lot of books, and in little more than a year, I have

just about hit capacity. What this means is that when I buy new

books, I have to let a couple go. This isn't all bad news; the culling

process is good discipline, as it forces me to review the collection

periodically, asking myself whether a given book is now obsolete

(DOS, anybody?) or otherwise unnecessary. When

I built my house here, I set myself an interesting challenge: To

keep my three largest and most-used book categories (computing,

religion, and general reference) in my office, and limit myself

to what will fit on the shelves. I have a lot of shelves in this

one room (what you see at left is only about half of them) but I

also buy a lot of books, and in little more than a year, I have

just about hit capacity. What this means is that when I buy new

books, I have to let a couple go. This isn't all bad news; the culling

process is good discipline, as it forces me to review the collection

periodically, asking myself whether a given book is now obsolete

(DOS, anybody?) or otherwise unnecessary.

Of course, with ebooks I wouldn't have to bother. I have a few

ebooks here, and they're small. Even with graphics, a typical

technical book is generally smaller than your typical MP3 file,

down in the 2-3 MB range. Novels or purely textual nonfiction are

smaller still, often smaller than 1 MB, with much of that taken

up by the cover bitmap. Assuming an average size of 2 MB, that's

500 ebooks per gigabyte of storage. 4 GB USB flash drives are now

commonplace, and getting cheaper. That's 2,000 ebooks in something

the size of your little finger, which is more books total than

I have here in my entire house. If you can set aside 20 GB of your

laptop's hard drive for ebooks, you can carry 10,000 ebooks in your

briefcase—and I'm sure I haven't read nearly that many books

in my entire life.

I like print, and I think it will be with us for a long time to

come. But packrat that I am, being able to deep-archive marginally

useful print books as ebooks would be nirvana. If I ever really

need a book on DOS, well, I'd still have it.

So why aren't ebooks the Next Big Thing? When will they break out

of the Early Adopter Ghetto? Let me spend a couple of entries talking

about that.

Overview: There are three serious problems with ebooks:

- The reading experience is still painful.

- Proprietary formats still dominate

- File-sharing makes publishers hesitate, or tie up the product

with unacceptable DRM.

Tomorrow I'll begin by talking about why reading ebooks is still a

headache—and why this is by far the easiest problem to fix.

|

September

16, 2005: Cover Art for The Cunning Blood September

16, 2005: Cover Art for The Cunning Blood

The

most amazing Todd Hamilton has turned in the cover art for my novel,

at left. (Cover text has not yet been merged with the image.) Those

who have read the story will almost certainly recognize the various

motifs; everybody else won't have to wait long: It should be off

press and in our hands by November 10 or so and will be available

in quantity shortly after, especially if you'll be at Windycon

in Chicago on November 13. The

most amazing Todd Hamilton has turned in the cover art for my novel,

at left. (Cover text has not yet been merged with the image.) Those

who have read the story will almost certainly recognize the various

motifs; everybody else won't have to wait long: It should be off

press and in our hands by November 10 or so and will be available

in quantity shortly after, especially if you'll be at Windycon

in Chicago on November 13.

The book will be a dustjacket hardcover, 360 pages, printed by

conventional offset press at Thomson-Shore near Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Cover price has not yet been set. It should be available from Amazon

and will have (I hope) some reasonable presence in Borders and Barnes

& Noble. Certainly you'll be able to order it from any reasonable

bookstore, and once the ISFiC

Web site is finished (it's still a little sparse, but I know

that Steven's working on it) you will also be able to order it direct

from the publisher.

I wrote this so long ago and tried to sell it for so long that the

whole adventure had begun to feel completely unreal. Suddenly, after

seven long years, it seems mighty real.

|

September

15, 2005: The Great Threat to Copyright September

15, 2005: The Great Threat to Copyright

In most recent articles about DRM, the big content companies invariably

bemoan the fact that "nobody respects copyright anymore."

Setting aside the question of how serious the problem actually is,

the question I'd rather see answered is, How did this come about?

I have a theory: Copyright is increasingly seen by ordinary people

as something benefitting only a few wealthy people and companies.

This suspicion was growing even before scorched-Earth DRM systems

put targets on the heads of paying content customers. For quite

a few years (I would say since the early 1980s) various market forces

have gradually been turning the content industry into a "winner-takes-all"

game in which a few players get hugely wealthy, and players on the

fringes get little or nothing. Part of it is retail concentration

and the death of quirky, locally controlled media retailing; part

of it is the concentration of attention that the mass media bring

about; and part of it are new laws that give much stronger legal

protection to media that only the wealthy can afford to prosecute.

I first heard the term "mansion trash" years back when

newly rich country star Garth Brooks started bitching about used

CD sales (not piracy!) and how trading in used CDs should be illegal.

When people like Brooks so obviously hold their audiences in contempt,

it shouldn't surprise anyone that people begin to hold Brooks' copyrights

in contempt. When people who pay for content feel like copyright

restrictions and DRM are tightening around their necks like a noose

(and making their grip on the content they paid for weaker and weaker)

it's natural that they feel like they're being ripped off, prompting

wholesale disregard for the rights of content creators.

I'm not saying that it's right. I'm saying (as a holder of several

paying copyrights) that it's dangerous. Great concentrations

of wealth and power eventually provoke populist responses. The personal

income tax was made constitutional in 1913 almost entirely to punish

the wealthy Northeast. If we ever do see another populist revolt against

concentrations of power, the entire concept of intellectual property

may go into eclipse. The very fact that some people reading this are

probably saying to themselves, "so what?" indicates that

we're already a long way down that very foggy road.

|

September

14, 2005: Activation's Core Problem September

14, 2005: Activation's Core Problem

I'm a little surprised, but a couple of people didn't get the gist

of my September 8, 2005 entry. I have

several issues with product activation, but the primary reason I

don't use activated products myself is that they can't be trusted.

As Jerry Pournelle pointed out over 25 years ago, copy protection

is a bad idea because it makes software fragile. It may be true

that the programmers who created Adobe's activation system didn't

intend for it to conflict with striped RAIDs, but software, as with

any species of complex system, is full of unintended consequences.

Today's it's striped RAIDS. Tomorrow...who knows? Multiprocessor

systems? Multicore processors? Hardware-assisted virtualization?

I'm not going to put time and what's left of my hair on the line

to debug what amounts to a weapon aimed at my own forehead.

As long ago as late 2000, I

ran afoul of an early scorched-Earth DRM system in an ebook

reader called Glassbook. The damned thing wouldn't let me run a

debugger while it was in memory, and there was no way to get it

out of memory short of rebooting. For all the praise heaped on it,

and Adobe's acquisition of the technology in 2000, Glassbook has

since bought the farm, and it's unclear whether Glassbook formatted

ebooks can be read on any other reader. (This is yet another problem

I have with DRM technologies: What happens to orphaned DRM systems

and content?)

As I said in my September 8 entry, activation is only used by companies

that are so prosperous that they can annoy their paying customers

with impunity. Pirates can and have cracked every activation scheme

I've researched, so the only people who take the hits are people

who pay for the software and try to play by the rules.

Again, no thanks.

|

September

13, 2005: Odd Lots September

13, 2005: Odd Lots

- Whew. As best I know, my part in the publication of The Cunning

Blood is finished, and the book should be off press by November

10 or pretty close to that. (That's why I've been missing days

here. Many things collided in a single time period.) The book

will be introduced at Windycon

in Chicago on the 13th. I'll be there. Do let me know if you will

be too!

- Gallery 2.0 was released

today. That's the PHP server-side photo manager that handles my

albums at gallery.duntemann.com.

I'm extremely impressed with Version 1, and will be upgrading

to V 2.0 some time in the next few days. So if the albums don't

come up right away, it may mean I'm messing with the software.

Check back later.

- Pertinent to the above, the most-viewed photo in the Jeff &

Carol album is the 1971 shot of me in that nearly indescribable

psychedelic suit, and Carol in a miniskirt. Why do I think it's

not me that everybody's rushing to see?

- I just replaced a 1995-era Pentium I machine over at our church

with something current, and the old machine (166 MHz) is going

to be scrapped. In older days I would be wondering about how to

render data on the hard disk unrecoverable (it contains records

of church membership, donations, bills, etc.) but it occurred

to me that there's not a great deal of use anymore for a 1 GB

hard drive. Therefore I'm going to do what I call a "mummy

unwrapping" next week and literally take the drive apart

piece by piece, not only to render its data unreadable, but also

to recover those wonderful strong little rare earth magnets that

help move the read/write heads. It's odd to think that a 1 gigabyte

hard drive is now so small as to be worthless, but true's true.

If it weren't for the magnets, I'd use it for target practice

with my sledgehammer.

- I learn interesting new words in odd ways. While spell-checking

a document the other day, my spell-checker barfed on the word

"scannable" and suggested "scumble" instead.

This is a real word, meaning "to apply a thin layer of semi-opaque

paint over a color to modify it." I used to regularly type

"cerate" instead of "create" and was in my

thirties before I discovered that "cerate" means "to

coat with wax." Egad, English has a word for everything.

- Pertinent to the above, I learned another peculiar word last

week—and then in the heat of a very busy week forgot what

it was. The word meant "eloquent praise of worthless things."

It's a rare word (else I would have heard it before I was 53)

and even a fair amount of googling has not turned it up.

|

September

11, 2005: Why I Didn't Self-Publish My Novel September

11, 2005: Why I Didn't Self-Publish My Novel

As I mentioned briefly a few days ago, my SF novel The Cunning

Blood is going to be published in November by a startup press

outside Chicago. I wrote the book in my loose moments from the end

of 1997 to April, 1999. I shopped it for several years and got nowhere.

Some of the big houses were polite, and looked at the manuscript.

Most were polite and said, we're overbought right now. (With the

implied: Come back ten years ago.) The rest didn't even answer

my emails. So the book just sat for a couple of years doing nothing,

and I strongly considered publishing it myself. After all, I know

how it's done, heh.

Well, I didn't, and a number of people have asked me to explain

why.

First of all, some very knowledgeable people told me not to—people

with the stature of Nancy Kress and Darrell Schweitzer. I confess

that as well as I know the mechanics of publishing, I don't know

the SF book market very well, and I'm smart enough to listen to

people whom I consider experts in the field. They told me that self-publishing

marks you as an amateur for life, irrespective of how good your

material is. This is less than completely clear to me, especially

given that Christopher Paolini self-published his fantasy novel

Eldest, and now

that Random House has picked it up, nobody's calling him

an amateur.

I know, I know, there's one Christopher Paolini for every ten thousand

wannabe self-published novelists. Am I so bold as to assume that

I'm the next one in ten thousand? On a good day, maybe. But my real

reasons lie elsewhere.

Basically: I don't like the way most of the big presses operate,

not only in SF but in other areas as well. The accountants are running

the show, and the SMOWS (Sell More Of What Sells) imperative gradually

narrows the field within which the front-line editors can move until

there's almost no originality in the lineup. Harry's big this year,

so elves'n'gnomes are big, or anything else that would appear to

ride on Harry's coattails. To deviate from SMOWS requires a very

big name.

This is certainly true of computer books, and from I've heard it's

even worse in SF/fantasy.

I don't expect to make much money on the novel, and I don't have

to live off the proceeds. That allows me to work with a publisher

that actually knows the field and the audience, and do my part encouraging

what I think is the future of quality book publishing: small presses

that know their topic area and remain close to their audiences.

Besides, self-publishing is work. This way, I free up enough

time to (gakkh!) write another novel, and now that my first is no

longer moldering on the shelf, I'm good with that.

|

September

10, 2005: Odd Lots September

10, 2005: Odd Lots

- I stumbled across a

great little set of JavaScript calculators focused on "space

math." You can calculate orbits, speeds for both Newtonian

and relativistic travel, rotational speeds of space habitats given

their size and desired level of artificial gravity, and so on.

Man, I could have used this thirty years ago—and with some

luck, I will need it again in the near future. Fine stuff.

- Another handy page summarizes

the HTML document character set. If you need to find out how

to insert special symbols (daggers, math symbols, em/en dashes,

foreign language characters, etc.) this page provides a nice summary.

- We're seeing some

increased solar activity (more

info) the last few days, so those of you living life in a

northern town, look out your windows on the next few clear nights.

We are expecting aurora borealis as far south as (yes!) Colorado.

- This one's for tube radio freaks, and low-voltage tube radio

freaks in particular: Jim Strickland sent me a link to a

page focusing on the "Hikers" radios of the 1930s,

which used low-voltage batteries and are thus not a shock hazard.

The page is detailed and includes a lot of scans of the original

construction articles, but it's extremely IE-specific, so if it

looks weird using another browser, you'll have to swallow your

bile and fire up IE.

- I put up a second album on gallery.duntemann.com,

this one with photos of Carol and me down through the years, starting

when we met in 1969. It's just for fun; to see a picture of me

with hair, or Carol in one of those 1970s miniskirts, that's the

place to go.

|

September

9, 2005: Donating Carefully and Effectively September

9, 2005: Donating Carefully and Effectively

I may be the last one in the blogosphere to have said this, but

it bears repeating: Be careful where you send money to benefit

the victims of hurricane Katrina. Scammers and phishers jumped

in almost immediately, and the Web is full of "Donate here!"

links, almost all of which are legitimate. But how can you

tell which is which?

It's not easy, especially since many completely legitimate charitable

agencies have formed in the last couple of weeks specifically to

help victims and refugees. You won't find anything on them because

they're too new. That doesn't mean they're bogus or inefficient.

In fact, some of these brand new efforts are working very well because

they're small, local, and not burdened by huge bureaucratic organizations.

Church relief agencies are also generally effective, because charity

has long been the business of (legitimate) religion. If you belong

to a large church organization, see if there are any efforts active

in Katrina relief. The Catholics and Baptists have extremely effective

organizations, and the Episcopalians are right up there. These are

just the ones I know are active; other churches may well be. If

you don't have a church or aren't interested in organizations within

a religious framework, the American Red Cross can certainly be trusted.

I find the local groups working outside of the disaster area to

receive and help settle refugees especially interesting. If everybody

descends on New Orleans it will be chaos. The real challenge is

getting people out of there and into some sort of functional life

situation somewhere, either permanently or until New Orleans is

fit to live in again. They're everywhere; ask around. You may know

some of the people involved, and that's the best way to determine

if they're legitimate (they probably are) and effective—which

is more of a challenge since many are composed of people with little

or no experience in this kind of service.

One of these local agencies that I will vouch for is PADS: Public

Action to Deliver Shelter. It's located in south suburban Chicago,

and is focused on using the old Tinley Park Mental Health Center

as a temporary shelter for Katrina refugees. The Chicago

Tribune covered it a few days ago. I trust PADS because the

Rev.

Mary Ramsden, an Old Catholic priest, is in the center of it

all, working with the sort of furious energy that only saints-in-training

can bring to bear on humanitarian efforts. She knows how it's done,

and she's been doing it most of her adult life.

PADS doesn't have a Web site yet. Contributions are always welcome;

make checks out to "South Suburban PADS." Checks should

then be sent to:

The Rev. Mary T. Ramsden

5520 South 72nd Court

Summit IL 60501-1203

I'm encouraged by the incredible outpouring of money and energy from

ordinary people to Katrina's victims, in stark contrast to various

government agencies, which can't seem to get out of their own (and

one another's) way. Government doesn't care. Government can't

care. Only individuals care, and every time I start edging toward

cynicism, ordinary people are the ones who slap me out of it.

|

September

8, 2005: Who Benefits from Activation? September

8, 2005: Who Benefits from Activation?

Silly question, actually. Product activation is touted as software

vendors' only defense against bankruptcy at the hands of software

pirates, but I find it notable that the only companies that use

activation are those that dominate or even monopolize a product

category. Microsoft is the most visible user of product activation,

but Adobe and Macromedia use it as well, and Adobe's system appears

to be much touchier than Microsoft's.

Case in point: Adobe's recent product releases don't

like RAID arrays, and assume that each RAID drive is a separate

PC. I find this mind-boggling. Was this the consequence of putting

moron-level programmers on the job? Or does Adobe just not care

what problems they cause paying customers, so long as they reduce

their piracy rate to zero?

We're dealing with Right

Men again, who will go to any lengths to get their way, even

if it means losing money they would otherwise have made. I bought

InDesign 1.5 and Acrobat 4 some years ago, and use them happily

to this day. I would have upgraded to more recent releases, but

I won't if the software is hair-trigger ready to stop my work in

its tracks. Adobe therefore loses a significant amount of money

they they would definitely have received from me. How much they

lose from piracy is a difficult question, because not every pirated

copy is a lost sale. But nobody ever seems to talk about how much

money Right Men lose by screwing over their legitimate customers.

The RAID problem isn't the core issue. A product activation scheme

that will call a RAID array a group of separate PCs will do other

stupid things. Forget it.

Small software companies trying to stay alive don't fool with product

activation. Only companies that are almost completely secure in their

respective markets can risk losing money they would have made from

customers who (very understandably) won't allow their software to

hold their work hostage. This actually does damage to the whole idea

of copyright, as I will explain in a future entry.

|

September

7, 2005: Odd Lots September

7, 2005: Odd Lots

- Stumbled across Mike's

Classic Cartoon Themes while researching Colonel Bleep, a

slightly surreal limited animation cartoon we used to see on the

Garfield Goose show in Chicago in the late 1950s. Virtually all

the cartoon shows I remember are there, with the notable exception

of Tom Slick. Lotsa fun.

- I like good tech hoaxes, and this

is one of the best I've seen in a while.

- The SF story I was reaching for in my September

4, 2005 entry was "Who Steals My Purse" by John

Brunner. Cool cover. I don't have the

mag yet but will eventually find it somewhere.

- You want to see some spectacular astrophotography, try this.

And with an 11" scope and a Webcam! The page speaks for itself.

Thanks to Pete Albrecht for the link.

- Brad Thompson points out that New Orleans has more

to worry about than dirty water. I duked it out with termites

once, back when I was in Arizona. I had a pile of duplicate ham

radio mags on the garage floor, and they hollowed it out and turned

it into Termite City. Interestingly, we used the same techniques

the chap here describes, which are not new—though admittedly,

I was not fighting Formosan Super Termites. (Maybe they'll all

drown.)

|

September

6, 2005: That Damned Tone Control September

6, 2005: That Damned Tone Control

Well,

last night I may well have finished my 6T9 tube stereo amp—depending

on how you define "finished." By mid-August I had finished

wiring the first audio stages and the balance control. I tested

the amp then, and it was glorious. It only puts about 1.7 watts

per channel, which doesn't sound like much by headbanger standards,

but it fills my workshop very nicely. I tested it with single-tone

audio from my audio generator, and then with music from MP3s played

on my laptop beside it on the bench. At one point I had some very

slight instability at about 150 Hz on the left channel, but re-dressing

some wires made it go away, and I haven't heard it since. I may

have a borderline ground loop problem somewhere. Whether I decide

to chase it depends entirely on whether the instability returns.

If it does, I know where to look. Well,

last night I may well have finished my 6T9 tube stereo amp—depending

on how you define "finished." By mid-August I had finished

wiring the first audio stages and the balance control. I tested

the amp then, and it was glorious. It only puts about 1.7 watts

per channel, which doesn't sound like much by headbanger standards,

but it fills my workshop very nicely. I tested it with single-tone

audio from my audio generator, and then with music from MP3s played

on my laptop beside it on the bench. At one point I had some very

slight instability at about 150 Hz on the left channel, but re-dressing

some wires made it go away, and I haven't heard it since. I may

have a borderline ground loop problem somewhere. Whether I decide

to chase it depends entirely on whether the instability returns.

If it does, I know where to look.

Anyway. The sound was great, but it was a little shrill, especially

on some of those 60s "hits" that were mixed to emphasize

the highs, for reasons I've never entirely understood. The last

things I wired in were the tone control components, and that's when

it hit the fan.

Troubleshooting is actually part of the fun in this game, and I'm

not sure I would have been completely pleased had the amp worked

flawlessly the first time I tried it. With the dual tone control

pot in place, one channel was dead...and the other was unaffected.

No matter where I swung the tone pot, the frequency mix on the left

channel didn't change.

The

dead channel was the easy one. I had left the solder tip on one

end of a run of RG 174 a little too long, and because there was

some bend in the run, the center conductor migrated through the

softened insulation and touched the shield braid, grounding the

signal input to the second audio stage. That was simply bad construction

on my part. I should have cut the braid back another 1/4". The

dead channel was the easy one. I had left the solder tip on one

end of a run of RG 174 a little too long, and because there was

some bend in the run, the center conductor migrated through the

softened insulation and touched the shield braid, grounding the

signal input to the second audio stage. That was simply bad construction

on my part. I should have cut the braid back another 1/4".

After I fixed that, both channels worked...but the tone control

did nothing. It took an hour of hard thought and some flipping through

a couple of 50-year old tube-era radio servicing books, but at last

I realized that tone controls are really touchy things.

The circuit first appeared in the 1965 GE Electronic Components

Hobby Manual, which was an assemblage of circuits from GE's

engineering staff intended to promote use of their parts. Tone control

circuits work by using a pot to shunt in capacitance that will pass

high audio frequencies but not low audio frequencies. Too low a

capacitance will shunt no audio at all (making the control ineffective)

and too high a capacitance will shunt all audio to ground,

leaving nothing for the power stage to amplify. GE had specified

750 pf for the shunt cap, which puzzled me. At 10,000 Hz (which

is the range you want to attenuate a little to let the bass be heard)

750 pf has a reactance of 21,000 ohms. Nothing much is going to

go through that until you go past 20,000 Hz or so, and human beings

can't hear that high.

So what's shown in the books? It's all over the map, and I don't

understand audio well enough to try to work through any equations.

My tube-era books that discuss tone controls specify values from

100 pf to .05 uf. Um, that's quite a range. Since the books

could not provide a consensus, I just closed my eyes and picked

something in the middle somewhere. I tacked in a couple of small,

modern .02 uf monolithic caps. This time, the tone control worked—too

well, actually. At minimum resistance, most of my signal (both treble

and bass) was going to ground, and volume fell off to almost nothing.

Too much capacitance. I tacked in some 005 uf caps, and the high

frequencies didn't come down quite as much as I wanted, but at least

the tone control wasn't pretending to be a second volume control.

.01 uf was a nice compromise, and while I could probably fool with

it for a few more weeks, I think I'll leave it where it is. I have

an intuition that .00750 uf might have been perfect—could the

GE guys have dropped the decimal point? Or did the publisher of

the book do it? There's no way to know. If I can find a couple of

good quality .008 uf caps I'll try them. In the meantime, I have

a pretty fine amp, and while I won't claim that it's "high-fidelity,"

it's just the thing for playing that scratchy rock'n'roll, as Joni

Mitchell was telling Carey back when I was in college.

The updated schematic in TIF format (originally drawn in Visio 2000)

is here. As time allows, I'll take voltage

readings at key points and add them to the schematic.

|

September

5, 2005: The Two Kinds of Disaster September

5, 2005: The Two Kinds of Disaster

Pertinent to yesterday's entry, I need to make clear that there

are two entirely different kinds of disaster: Acute disaster, and

chronic disaster. Acute disaster is something that happens quickly,

and is amenable to repair. Chronic disaster is something that develops

over a period of time, and is often extremely difficult to

put right. Acute disaster is a failure of expected circumstances.

Chronic disaster is a failure of the underlying system.

Natural disasters, like those caused by volcanoes, earthquakes,

and hurricanes, are classic examples of acute disaster. We don't

expect them, though perhaps (as with earthquakes along the San Andreas

fault, and hurricanes in New Orleans) we should. Sometimes, as with

the Great Influenza of 1918, acute disaster comes straight out of

left field and blindsides us all.

Chronic disaster is the result of cultural or governmental systems

that have for whatever reason ceased to work. The anarchy in Somalia

is probably the best example I could cite, though there are others

to be found, especially in sub-equatorial Africa. This kind of disaster

can be corrected (think of the famine in Bangladesh in the 1970s)

but it generally takes a fundamental change in culture, government,

or both.

There are cases that fall somewhere in the middle. AIDS, like any

deadly disease, might have been stopped in its tracks in the mid-1980s,

but it collided with a radical reorganization of sexual conventions

in the first world, and became parasitical on Western urban culture.

The Great Depression was the consequence of worldwide economic nationalism

that might have continued for decades had not World War II turned

the developed world inside out.

The key is to recognize that chronic disaster isn't usually amenable

to change from outside. We can fix New Orleans (how to fix it, and

to what extent it should be fixed, and—most important of all,

who pays for the fixing—are separate issues) but by this time

it's pretty clear that we can't fix Africa, or Iraq, and we will

probably make things worse by trying. (Whether we must try

when people are dying is one of the thorniest and most painful ethical

problems that any of us are facing right now.)

Nonetheless, there is hope, even for chronic disaster. Communism

was a chronic disaster for Russia, and it took 70 years for things

to even begin to move in the right direction. (They will be moving

in that direction for a long time yet.) India and China are moving

in the same direction, and far more quickly, even though they've

corrected their own disasters by exporting some of it to us.

Being open to change is the key. Brittle things are the seeds of disaster.

Thinking outside the box often lets you out of the box. Holding on

to the box just means you stay in the box, even if somebody cuts a

hole in the box and tries to wave you out.

|

September

4, 2005: When Helping is Selfish September

4, 2005: When Helping is Selfish

Time and again, liberal pundits, theologians, and other assorted

folk on the left lambaste Americans for not sending more aid to

Africa. This is a constant theme at the

Live 8 concerts, where multimultimillionaire rockers and movie

stars scream their indignant fury at the American middle class for

their selfishness.

Nobody (especially our liberal media) seems to want to discuss

the possibility that all the money and donated goods streaming into

Africa are a significant part of Africa's current problems. Here

and there I see some

press on the topic, and back in July, Der Spiegel (a

German newspaper) published an

interview with Kenyan economist James Shikwati, who basically

pleads for the West to "just stop." (Alternate

link; Der Spiegel can be fussy.)

We're killing them with kindness—if kindness is what it really

is. In 1997, 137,000 people were employed in Nigeria's textile industry.

In 2003, the figure had dropped to 57,000, due to shiploads of donated

clothing from the West. Loose supervision of aid monies allows corrupt

regimes to make off with, or simply waste, what is sent.

The engine behind fuss of the Live 8 sort is guilt: We can feel

better about our abundance by sending a little of it to poor Africa.

It's not about the Africans. It's about us. We don't need

that old Jersey anymore, so put it on the boat with tens of thousands

of other jerseys. We get a clear conscience, and Africa gets so

many jerseys that its own clothing industry withers and dies. Somehow,

nobody ever talks about that.

The one thing that would undeniably help Africa is the one thing

that the left will not consent to do: Throw open our borders

to African-made goods and food. Big labor will have none of that.

(Nor will Big Farming and many other groups that lean right, but

the left never offends its benefactors, even when it would

make ideological sense to do so.) In fact, as this

article indicates (usual idiotic newspaper signup required)

we have jiggered debt relief for nations such as Ghana in terms

that force them to reduce tariffs on heavily subsidized American

and European farm products, which bankrupts African farmers and

indigenous industries.

I vaguely recall reading an SF story in Analog when I was

in college about us knocking over a Vietnam-like nation by air-dropping

on it all the things they make locally, thus bankrupting the country.

(Does anybody remember that story? I think it was the cover story,

and would have been in '72 or '73.) We're doing that to Ghana right

now; basically dropping subsidized chickens and rice on them, and

we're not even at war with them.

The ugly truth may be that ordinary people like you and I are powerless

to help Africa. Generosity cannot help them. Debacles like Iraq suggest

that military intervention won't help them. Accepting their goods

may help a little, but unless African nations somehow create governments

and cultures that allow local economies to thrive, Africans will continue

dying. We can't transform their governments for them. The least we

can do is stop donating them to death.

|

September

3, 2005: Ecoterrorism Via Model Rocketry September

3, 2005: Ecoterrorism Via Model Rocketry

Pete Albrecht and I have been model rocket hobbyists for a great

many years—me, since senior year high school at least. It pains

me to see knucklehead government officials, especially in our school

system, positively freak out at the very idea of a rocket-powered

toilet paper tube with a balsa-wood nose. Good lord, with a weapon

of such awesome power you could destroy...you could destroy...well,

you could probably destroy something. (Certainly, you can

destroy the composure of a great many fools in powerful places.)

It's gotten so bad in some cities that you have to belong to a club,

or notify the police, before launching a model rocket anywhere.

Now

we have this.

A group of hugely righteous green-types in Holland have apparently

developed a system based on model rocket technology for delivering

herbicide-tolerant weed seeds into farmers' fields as a way of protesting

genetically modified crops. (Oh, the irony.) Because gasoline

is itself ecologically damaging, you have to pedal your way to the

offending field before pushing the button. Now

we have this.

A group of hugely righteous green-types in Holland have apparently

developed a system based on model rocket technology for delivering

herbicide-tolerant weed seeds into farmers' fields as a way of protesting

genetically modified crops. (Oh, the irony.) Because gasoline

is itself ecologically damaging, you have to pedal your way to the

offending field before pushing the button.

I thought at first that it might be a hoax, but judging from the

other items on their site I suspect it's serious. (However, note

that nowhere do we see a photo of the rocket actually being launched.)

Now when local officials here set out to ban model rocketry (to

prove that they're not "soft on terrorism" and actually

earning their keep) they can present the Dutch bicycle-mounted ecoweapon

to prove that somebody, somewhere, is using model rockets to commit

terrorist acts.

Hoax or not, it's actually pretty funny. How long do you think this

guy would last pedaling his way down a street in Washington, DC, or

any other major American city?

|

September

2, 2005: Is New Orleans History? September

2, 2005: Is New Orleans History?

New Orleans is indeed history, and that's its biggest problem.

Even if we manage to pump untold millions of gallons of sewage-laced

water from the heart of this lower-than-sea-level city, we have

to consider what happens next: A huge part of New Orleans'

beloved Creole architecture will have to be razed. As this

article suggests, old buildings that sit mostly submerged in

sewage for more than a few hours almost always have to be gutted

to the frame and rebuilt, and even then the frame isn't a sure thing.

In other words, New Orleans may well rise from the muck—but