|

|

|

|

|

Jeff's Home Page

|

Way back in 1960, I was in Woolworth's with a dollar to spend, and I spent it on a little hardcover book called Tom Swift and His Electronic Retroscope. I was eight years old but "advanced for my age" (as the nuns always said to my parents) so the transition from grade schooler SF to "preteen" SF was smooth and right on time. Prior to that day, I had gotten grade school books like Space Cat and The Enormous Egg from the Chicago Public Library, but all at once I was in another universe entirely. I had three more dollars of discretionary cash in the mayonnaise jar under my bed, and in the next couple of weeks it all went into three more Tom Swift books. For the next several years, until I got into high school and moved on to the next level (Heinlein and Asimov juveniles, and Arthur C. Clarke) Tom Swift for me was synonymous with science fiction. Most Americans know the name "Tom Swift" without really knowing much about the books themselves. Tom Swift, Sr was a fixture in a long series of cheap books dating back to 1900 or so, when "dime novels" were such a scourge upon American families. (Ancient echoes of that distaste were the reason Tom Swift, Jr, Hardy Boys, and the others were generally not stocked by public libraries, well into the Sixties and in some places even today.) The technology was cruder then (Tom Swift and His Motorcycle) and the writing more oriented toward running around and getting in fights with truly stupid villains. When Grosset & Dunlap (in cooperation with the Stratemeyer Syndicate, a packager of juvenile books who owned Tom Swift, Nancy Drew, and others) launched the Tom Swift, Jr. series in 1954, the conceit was that the original Tom Swift had married his girlfriend Mary Nestor, survived to middle age, and now had a teenage son. Better still, the senior Swift was head of Swift Enterprises and filthy rich. His blonde offspring had all the tools, gadgets, and help he needed to make the most of his wizardry. For sixteen years, Tom Swift and his pal Bud Barclay tore around the Earth and to the outskirts of the solar system, defeating spies, consorting with aliens, and building the guldurndest things. Bones & GadgetryBack at Woolworth's on that fateful day, it was the cover that snagged me: Two teenage boys inside some sort of tomb, surrounded by a ring of sinister skeletons seated against a stone wall. The boys were ignoring the skeletons, and steering some kind of electronic gizmo that was apparently reading futuristic symbols from faded carvings on the tomb wall. In a nutshell, that was what ten-year-old nerds in 1960 dreamed about: Poking around in weird places, seeing gross things like dead bodies, and tinkering with electronics. There was no need to go further. It was all right there.

Tom Swift was perpetually eighteen, an age far enough removed from where my nerd friends and I were to be beyond understanding, but close enough for us to think we might just get there someday. He didn't seem to go to school, and there was no indication as to how he learned all he knew. Hey, he was a genius. My friend Larry could play any song he heard on the piano, immediately, with both hands—and had never taken a single lesson. He was just born with it. So, apparently, was Tom Swift. None of that bothered us at all. Similarly, it was no bother that Tom Swift as a character was almost completely devoid of distinguishing personality traits. He was brilliant, strong, patriotic, hard-working, and respected his parents—and beyond that was as featureless as a billiard ball. In one sense that was because Tom Swift was a sort of Halloween costume that we donned in our imaginations, and any specifics that clashed too strongly with our specifics might have made this identification difficult. (I had this problem with numerous other characters in later SF, which made me more a spectator than a participant in the action.) Grosset & Dunlap knew what they were selling, and it wasn't literature. Tom had a girlfriend, Phyllis Newton, the daughter of his father's sidekick Ned Newton. Bud Barclay dated Sandy Swift, Tom's year-younger sister, who had apparently inherited none of the Swift genius. Mercifully, Phyllis and Sandy did not figure much in the action, and the boys were rarely required to rescue them from any sort of danger. The girls' sole role, I suspect, was to provide a sort of "real-life" point of departure for adventures. Numerous titles began with Tom, Bud, Phyllis and Sandy on a double date, from which the boys would madly dash for spaceships or submarines when some mysterious circumstance intervened. Early on, the girls were, to us, simply a needless annoyance—and later, when we were newly pubescent but still clueless nerds, they reminded us somewhat painfully that we were still sitting at home alone on Saturday nights reading Tom Swift books. There is only one fleshed-out (as it were) character in the Jr. canon: Chow Winkler. Chow was a bald-headed, paunchy middle-aged ex-cowboy from Texas, complete with Texas drawl, ten-gallon hat and Texas-sized confidence. Chow worked as the cook on all Tom's expeditions, whether to the depths of the sea or all the way to the Moon. Always good for a laugh, Chow would often show his mettle in combat by throwing food in the path of a Brungarian spy and making the bad guy fall flat on his face. All other characters were either archetypes (like the professional paranoid security chief Harlan Ames) or forgettable names utterly without faces. Tom Swift, Sr. shows up too rarely and too briefly to affect much of the plot, except once in what is arguably the weirdest of all the Jr. titles: Tom Swift and the Visitor from Planet X. Tom is planning to communicate with a ball of "brain energy" sent from the unknown planet where live his "alien friends," and he has to build a robot-like machine to house the brain energy. To test the machine he sets out to whip up some artificial "brain energy" of his own, but Father steps in with a stern warning that only the Almighty can create true Brain Energy. That's OK, Dad, Tom replies; I'm only going to make some ersatz simulated brain energy. (I wish I could quote you the exact exchange—it's priceless—but that title is one of my collection that has disappeared over the past 30-odd years.) Ozzie Nelson should be glad he never had to have that particular conversation with Rick and Dave! The Machinery of WonderTom Swift's amiable blandness was no big deal, because at the heart of

things, we were all in it for the gadgets. Every book had at least one

major gadget in it, even the handful of books for which the gadget was

not the core of the book's title. I enjoyed them all, though some seemed

kind of pointless (like the Terrasphere from Tom Swift in the Caves

of Nuclear Fire) and one or two simply ridiculous, even from a ten-year-old's

perspective. Tom Swift's Spectramarine Selector was a kind of electronic

wallpaper remover for sucking scum o Other of his inventions were brilliantly conceived. Of all Tom

Swift's creations, none made my blood pound like the Challenger,

Tom Swift's major spacecraft, the central gadget for 1958's Tom Swift

in the Race to the Moon, with significant appearances in most of the

later space titles. There was nothing else like it in all SF: A house-sized

rectangular cabin held in a huge frame consisting of two perpendicular

circular girders (with the obligatory Fiftyish round holes) making it

look a little like a cubistic gyroscope. The circular girders were tracks

for numerous Repelatron radiators, which were satellite-dish shaped antennas

that radiated a Swift-discovered force that selectively pushed other things

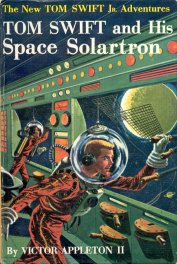

away. All of this inventing was done most casually, and the rest of the world beyond Shopton rolled sleepily on, without ever clamoring for the wonders pouring out of Tom Swift's labs. No one seemed to realize that any of several Swift inventions would have changed the shape of human history. In Tom Swift and the Cosmic Astronauts, Tom casually invents a gravity concentrator after repairing a kite for some younger kids in an empty lot, and in Tom Swift and His Space Solartron, he implements a gadget that converts solar energy directly to matter in the form of any chosen element or simple compound. (What he fails to take into account is the cruel equation E=MC2, and shows a couple hundred square feet of solar panel generating enough oxygen to fill a lunar dome in a few minutes.) The Repelatron alone would have changed the shape of technological society, as hinted but never fully explored in Tom Swift and His Repelatron Skyway. The author or authors seemed incapable of grasping the implications of what they wrote. In that title, Tom Swift lays "down" a floating superhighway in mid-air, to be supported on Repelatron beams, with a helicopter. Tom's creators didn't seem to hit upon the truth (as we all did, and discussed endlessly on Boy Scout campouts) that Repelatrons made all other forms of flying obsolete. We also realized that if the Space Solartron could convert solar energy to oxygen for breathing, to water for drinking, and even to sugar for eating, it could make gold as well. But Tom never hit on that. I guess he was rich already and wasn't ruled by crass financial motives. A Bill Gates he was not. As the series went on, the gadgetry became more and more implausible, and relied more on "mysterious" or "cosmic" forces that had the dark quality of magic about them. This, I suspect, was the outcome of trying to write a series of books about technological wonders in an age that was producing "for-real" scientific and technological wonders at an ever-accelerating clip. The desire to avoid "offending the known" is a problem in grown-up SF to this day, and accounts, I believe, for the current fascination with fantasy. We now know way too much to postulate "mysterious forces" with a straight face—unless they turn up in an archaic Anglo-Saxon wilderness where all the weird people have Welsh names. Finally, for all his brilliant innovation, Tom Swift failed to foresee the one thing that hit us all in the face like a cosmic cream pie in the mid-1970's: The personal computer. Computers were glaringly absent from the Swift canon. Here and there was an electromechanical calculator, and also an occasional slide rule. The rest of it Tom seemed happy to do in his head. We didn't mind. Math wasn't half as much fun as chasing spies most of the way to Mars. "The Missle Streaked Toward Them at Astonishing Speed!"I think the word "breathless" was coined to describe the writing in the Tom Swift, Jr. series. The omniscient narrator was an excitable deity, apparently, and really got into the telling of the tale. The books are full of copy like the following: The enclosure was needed to maintain a stable atmosphere--without it, the osmotic air conditioner would no longer function properly! The atmosphere inside the bubble would become unbearably humid! Gosh! The narrator has obviously never spent any time in Miami! Beyond that one peculiarity, the writing in the series isn't half as bad as legend would have it. Almost entirely absent from the Tom Swift Jr. series are "swifties"—unintentional howlers resulting from adverbs substituted for conventional "said-book-isms." For example: "I hate cleaning fish," Tom carped. "Take his picture," Tom snapped. These may have been rampant in the original Tom Swift (Senior) series; I can't say, having read only one. Whoever really wrote the Jr. series seems to have learned his/her lesson. There is an occasional "Bud gasped" or "Chow grumbled," but in context (especially in a juvenile) it all makes sense. My take is that the writing in the series is far better than in today's pure tonnage juvenile series like Goosebumps, but like everything else in the series, it is the product of another culture, one pre-1965 and forever in a state of (breathless) innocence. The Art of ExcitementThe drawn art sprinkled through the Tom Swift, Jr. series was a welcome respite from the writing—and the covers were nothing short of marvelous: Color, action, exotic locales, and of course the central invention, all executed in a space four inches by six. Illustrator Graham Kaye was very much the creator of the Tom Swift "look" and his several successors could only attempt imitation. Kaye did the first 20-odd books in the series with a strong and very Fifties illustrative style: crisp, literal, with a solid line and good use of shadow and solid areas. The artists who followed Kaye used a lighter touch, and were not the technicians that Kaye was. Ray Johnson, in particular, delivered something more a rough sketch than a true illustration, though his frontispiece for Tom Swift and the Mystery Comet is a reasonably accurate visual rendering of the beloved Challenger, something all too rare in the series. In the books that appeared toward the end of the Sixties I got the impression that the artists didn't quite know how to draw—or could no longer stand the thought of— a proper crew cut.

Another oddity was that the spaceships and other vehicles on the cover usually looked much smaller than they actually were, as described in the text. I suspect that there was some publisher's dictum that Tom and Bud had to be on every cover, in recognizable form. Show Tom's face through a window in the Challenger, and you won't see much of the Challenger--unless the artist compresses space a little and cranks down Tom's mighty spaceship to the size of a futuristic hotdog stand. The ultimate insult was the cover of Tom Swift and His Cosmotron Express, which has to show two spaceships, Tom and Bud in one, a bearded meanie in the other, plus between the two a couple of robot rockets locked in mortal combat. The Cosmotron Express is supposedly the "largest spacecraft ever built," but the two ships on the cover (both of them Tom's; the Bad Guy stole one) seem about twenty feet long, and indifferently drawn, at that. Cosmotron was the second-to-last of the series, so maybe by then nobody cared. The Face of a Hometown Wizard

This becomes all the more obvious when you compare Kaye's Swift to the redrawn images of the two paperback reprint series from the Seventies. The trade-sized Tempo Books paperback Tom Swift and the City of Gold from 1972 (a retitling of 1960's Tom Swift and His Spectramarine Selector, the scum-sucking whatchamacallit I rolled my eyes over even then) shows a pair of poker-faced youngsters who might be as much as fifteen at the controls of a submarine. My first reaction was, Who let those kids in there? They'll start messing with things and somebody's gonna get hurt... But the two kids heading for the City of Gold come way closer than the cherub on the back of the 1977 Tempo Books mass-market paperback reprint of Tom Swift and His Rocket Ship (below). Here we have a perfectly coiffed and extremely pretty twelve-year-old who seems lost in the grip of a mystical experience. C'mon, this is Super Science, not transcendental meditation—and that kid's not even old enough to drive.

The Last Boy GeniusBelieve it or not, in the early 1990's there was an attempt at yet another generation of Boy Genius Inventors: Tom Swift "III." The "III" is a collector's tag and appears nowhere in or on the books, and nothing is said about Tom Swift, Jr. having progeny. This new Swift is caught between two worlds, at least for me. He's trying hard to sound like a modern kid, and even plays basketball, but somewhere in there the genius gets seriously missing. And Bud Barclay has unaccountably vanished. Tom Swift and the Microbots (1993) throws in some techspeak on nanotechnology, but basically it's Tom Swift's Fantastic Voyage, in which technomagically shrunken teenagers dodge robot ants and other nonsense. I got about halfway through and realized that the party is indeed over. I don't think Boy Geniuses are part of our cultural mix anymore. Even the image of "boy" has changed radically; our 18-year-olds can vote and don't much care for the term as applied to themselves. Geniuses, too, are now politically incorrect—we're all equal no matter what we do, y'know? So bringing back Tom Swift as fiction is impossible—in the present there's no archetype, and the yayhoos in our universities have "deconstructed" the past to the extent that Tom Swift couldn't even be done as period fiction. But where poor Tom could still have a place is in cinema, which does far better evoking the Good Old Days. Two antecedents exist. The first is, of course, Raiders of the Lost Ark, which recalls the awful Saturday Afternoon serials of the Depression and WWII years. It was as beautifully done as the originals were crude, and it was superb at capturing the cultural feel of the times. The other and perhaps more evocative film is The Rocketeer, which better than anything else I've ever seen captured the mood of pop culture in 1937. Maybe the Fifties are too recent for that kind of nostalgia tripping, but Tom's time could yet come. I can imagine the Steven Spielberg rendition of Tom Swift and the Race to the Moon, complete with the Challenger, Chow Winkler, Repelatrons, 1957 Chevies, fish-bowl space helmets, flying saucers, malt shops, Cold War paranoia, and all the other trappings of that golden year 1958. A film like that could easily become the top-grossing movie of the year, which would at last say something significant about Tom Swift, Jr... ...and perhaps even more about us, who learned to dream by looking over his shoulder at the now-vanished universe of infinite promise. |

|

|

The Tom Swift, Jr. series: 1954-1971All credited to Victor Appleton, Jr.Many or most outlined by Harriet Stratemeyer Adams, and written either by her or by someone under her direction. Title Year Illustrator 1. TOM SWIFT and His Flying Lab 1954 Graham Kaye 2. TOM SWIFT and His Jetmarine 1954 Graham Kaye 3. TOM SWIFT and His Rocket Ship 1954 Graham Kaye 4. TOM SWIFT and His Giant Robot 1954 Graham Kaye 5. TOM SWIFT and His Atomic Earth Blaster 1954 Graham Kaye 6. TOM SWIFT and His Outpost in Space 1955 Graham Kaye 7. TOM SWIFT and His Diving Seacopter 1956 Graham Kaye 8. TOM SWIFT in the Caves of Nuclear Fire 1956 Graham Kaye 9. TOM SWIFT on the Phantom Satellite 1956 Graham Kaye 10. TOM SWIFT and His Ultrasonic Cycloplane 1957 Graham Kaye 11. TOM SWIFT and His Deep-Sea Hydrodome 1958 Graham Kaye 12. TOM SWIFT in the Race to the Moon 1958 Graham Kaye 13. TOM SWIFT and His Space Solartron 1958 Graham Kaye 14. TOM SWIFT and His Electronic Retroscope 1959 Graham Kaye 15. TOM SWIFT and His Spectramarine Selector 1960 Graham Kaye 16. TOM SWIFT and the Cosmic Astronauts 1960 Graham Kaye 17. TOM SWIFT and the Visitor from Planet X 1961 Graham Kaye 18. TOM SWIFT and the Electronic Hydrolung 1962 19. TOM SWIFT and His Triphibian Atomicar 1962 Charles Brey 20. TOM SWIFT and His Megascope Space Prober 1962 21. TOM SWIFT and the Asteroid Pirates 1963 Charles Brey 22. TOM SWIFT and His Repelatron Skyway 1963 Charles Brey 23. TOM SWIFT and His Aquatomic Tracker 1964 Edward Moritz 24. TOM SWIFT and His 3-D Telejector 1964 Edward Moritz 25. TOM SWIFT and His Polar-Ray Dynasphere 1965 Edward Moritz 26. TOM SWIFT and His Sonic Boom Trap 1965 Edward Moritz 27. TOM SWIFT and His Subocean Geotron 1966 Edward Moritz 28. TOM SWIFT and the Mystery Comet 1966 Ray Johnson 29. TOM SWIFT and the Captive Planetoid 1967 Ray Johnson 30. TOM SWIFT and His G-Force Inverter 1968 31. TOM SWIFT and His Dyna-4 Capsule 1969 32. TOM SWIFT and His Cosmotron Express 1970 Ray Johnson 33. TOM SWIFT and the Galaxy Ghosts 1971 |